The Cartographer of Radio Frequencies: Understanding the Spectrum Landscape

There's a peculiar solace in the hum of a well-tuned radio. It’s not just the voices, the music, or the news; it's the understanding that you’ve intercepted a signal dancing across the ether, a whisper carried on invisible waves. This feeling resonates with me profoundly, evoking memories of my grandfather's antique accordion. He’s gone now, but I still remember the hours spent listening to him play, the bellows sighing, the keys clicking – each movement a deliberate action, a precisely executed gesture to produce a cascade of sound. The act of radio communication, in a way, feels similar. It requires a level of skill, a deep appreciation for the nuances of the system, and a respect for the shared space that allows it to exist.

Unlike the beautifully tangible instrument my grandfather cherished, the radio frequency spectrum is an invisible realm. It’s a shared resource, a common ground for countless services – from emergency communications and satellite navigation to your favorite radio stations and, of course, ham radio.

The Spectrum: A Shared Highway

Think of the radio frequency spectrum as a vast highway, and each service as a vehicle using a designated lane. This “highway” extends from roughly 3 kHz to 300 GHz, encompassing a dizzying array of frequencies. Governments worldwide, through organizations like the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), manage this spectrum, assigning specific bands for particular uses. These allocations aren't arbitrary. They're based on international agreements designed to minimize interference and ensure that everyone can “travel” safely.

At the lower end, you have frequencies used for things like AM radio broadcasting (530–1710 kHz) and shortwave radio (typically 3–30 MHz). Higher up, you find FM radio (88–108 MHz), television broadcasting, cellular communication, and, crucially for many hams, the amateur radio bands.

Delving into the Bands: A Ham's Perspective

For the amateur radio operator, understanding these bands isn't just academic – it's a fundamental skill. The amateur radio bands are carefully allocated, allowing for experimentation, communication, and emergency preparedness. These bands include segments like 80 meters (3.5-4 MHz), 40 meters (7-7.3 MHz), 20 meters (14-14.35 MHz), 15 meters (21-21.7 MHz), 10 meters (28-29.7 MHz), and higher. Each band has its own characteristics in terms of propagation (how signals travel) and available power.

Lower frequencies, like 80 and 40 meters, propagate via the ionosphere, bouncing signals across vast distances. These bands are particularly valuable during periods of solar activity when the ionosphere is more active. Higher bands like 10 meters offer shorter-range communication but can be excellent during certain conditions. The constant variation makes radio an endlessly fascinating pursuit.

The Human Element: Craftsmanship and Care

Just as a skilled accordion repairman understands the intricate workings of a bellows, the mechanics of a reed, and the delicate balance required for a beautiful sound, a responsible radio operator understands the importance of respecting the spectrum. It’s not just about transmitting a signal; it’s about doing so responsibly and in compliance with regulations.

My grandfather wasn’t just playing an accordion; he was maintaining a tradition, demonstrating a respect for the craft. He would meticulously clean each reed, oil the leather, and carefully adjust the tension – a process born of both knowledge and a deep appreciation for the instrument. Similarly, ethical ham radio operation involves understanding regulations, minimizing interference, and respecting the rights of others who share the spectrum.

The Consequences of Disregard

Imagine a busy road where drivers disregarded traffic signals and lane markings. Chaos would ensue. Similarly, irresponsible use of the radio spectrum can create significant interference, disrupting critical communications and causing frustration for everyone. Harmonics, spurious emissions, and exceeding power limits are all common sources of interference.

The licensing process for amateur radio is designed, in part, to ensure that operators understand these responsibilities and are committed to using the spectrum responsibly. It's about more than just the right to transmit; it's about the privilege of doing so.

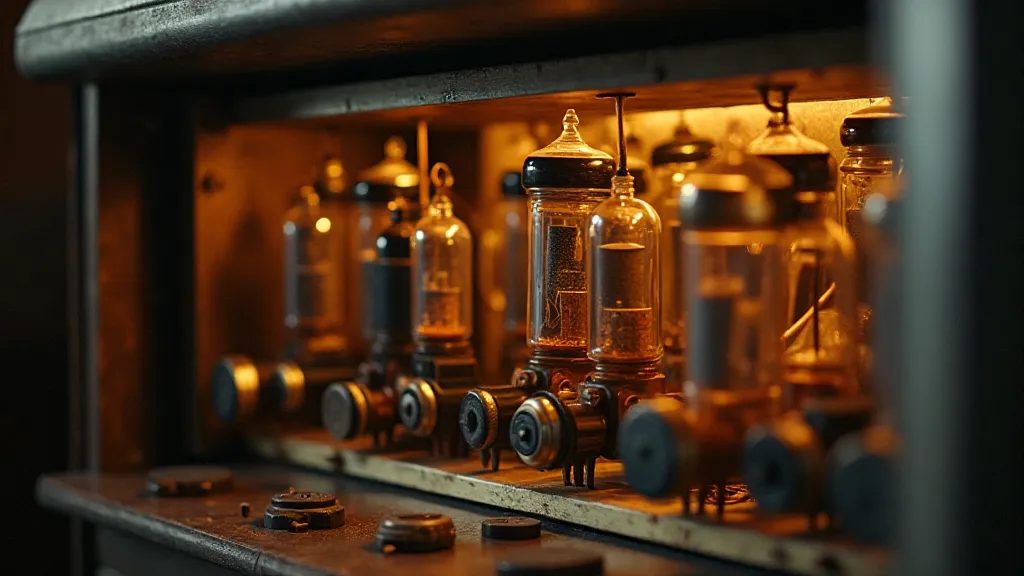

Restoration and the Analog Mindset

There's a certain appeal to the analog world, a satisfaction in understanding how things work from the ground up. Restoring an antique accordion, like building a simple transceiver, requires patience, a willingness to learn, and a respect for the original design. It’s a tactile experience that connects you to the past.

Many hams appreciate this same analog mindset. While digital modes offer their own advantages, the allure of building your own radio from scratch, understanding every component, and transmitting a signal with your own hands remains a powerful draw. The connection to the principles behind radio communication feels more immediate and satisfying.

Looking Ahead: The Future of the Spectrum

The radio spectrum is a finite resource, and its management is becoming increasingly complex. As technology evolves and new services emerge, the demand for bandwidth continues to grow. Innovation in spectrum sharing techniques, such as dynamic spectrum access, is crucial for ensuring that the spectrum can continue to meet the needs of society.

A Legacy of Communication

Understanding the radio frequency spectrum isn’t just about technical knowledge; it's about appreciating the legacy of communication and the importance of responsible stewardship. Like the care my grandfather put into his accordion, respecting the spectrum is a testament to our commitment to the community and the future of radio. It's a constant reminder that even invisible waves can create profound connections.